This part is going to be a bit dry, but necessary, I think.

Historically, the teaching of the Church regarding the Jewish people is known as Supersessionism, also known as Replacement Theology (which, despite the distaste for the term that some Supersessionists have, is a pretty apt translation of the term’s root supersede) and Fulfillment Theology.

According to Walter C. Kaiser, “Replacement theology . . . declared that the Church, Abraham’s spiritual seed, had replaced national Israel in that it had transcended and fulfilled the terms of the covenant given to Israel, which covenant Israel had lost because of disobedience.” Ronald E. Diprose defines replacement theology as the view that “the Church completely and permanently replaced ethnic Israel in the working out of God’s plan and as recipient of Old Testament promises to Israel.” R. Kendall Soulen argues that supersessionism is linked with how some view the coming of Jesus Christ: “According to this teaching [supersessionism], God chose the Jewish people after the fall of Adam in order to prepare the world for the coming of Jesus Christ, the Savior. After Christ came, however, the special role of the Jewish people came to an end and its place was taken by the church, the new Israel.” Herman Ridderbos asserts that there is a positive and negative element to the supersessionist view: “On the one hand, in a positive sense it presupposes that the church springs from, is born out of Israel; on the other hand, the church takes the place of Israel as the historical people of God.” . . .

When comparing the definitions of Kaiser, Diprose, Soulen, and Ridderbos with the statements of those who openly promote a replacement view, it appears that supersessionism is based on two core beliefs: (1) national Israel has somehow completed or forfeited its status as the people of God and will never again possess a unique role or function apart from the church; and (2) the church is now the true Israel that has permanently replaced or superseded national Israel as the people of God. Supersessionism, then, in the context of Israel and the church, is the view that the New Testament church is the new Israel that has forever superseded national Israel as the people of God. The result is that the church has become the sole inheritor of God’s covenant blessings originally promised to national Israel in the Old Testament. This rules out any future restoration of national Israel.1

At the other extreme is the position known as Dispensationalism, characterized by:

- Hermeneutical approach that stresses a literal fulfillment of Old Testament promises to Israel Though the issue of “literal interpretation” is heavily debated today, many dispensationalists claim that consistent literal interpretation applied to all areas of the Bible, including Old Testament promises to Israel, is a distinguishing mark of dispensationalism. . . .

- Belief that the unconditional, eternal covenants made with national Israel (Abrahamic, Davidic, and New) must be fulfilled literally with national Israel Although the church may participate in or partially fulfill the biblical covenants, they do not take over the covenants to the exclusion of national Israel. Physical and spiritual promises to Israel must be fulfilled with Israel.

- Distinct future for national Israel “Only Dispensationalism clearly sees a distinctive future for ethnic Israel as a nation.” This future includes a restoration of the nation with a distinct identity and function.

- The church is distinct from Israel The church does not replace or continue Israel, and is never referred to as Israel. According to dispensationalists, the church did not exist in the Old Testament and did not begin until the Day of Pentecost (Acts 2). Old Testament promises to Israel, then, cannot be entirely fulfilled with the church. . . .

- Multiple senses of “seed of Abraham” According to Feinberg, the designation “seed of Abraham” is used in different ways in Scripture. First it is used in reference to ethnic, biological Jews (cf. Romans 9—11). Second, it is used in a political sense. Third, it is used in a spiritual sense to refer to people, whether Jew or Gentile, who are spiritually related to God by faith (cf. Romans 4:11-12; Galatians 3:7). Feinberg argues that the spiritual sense of the title does not take over the physical sense to such an extent that the physical seed of Abraham is no longer related to the biblical covenants.

- Philosophy of history that emphasizes both the spiritual and physical aspects of God’s covenants. According to John Feinberg, “nondispensational treatments of the nature of the covenants and of Israel’s future invariably emphasize soteriological and spiritual issues, whereas dispensational treatments emphasize both the spiritual/soteriological and the social, economic, and political aspects of things.”2

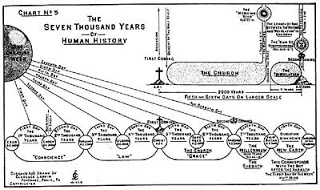

Dispensationalism gets its name from the belief that there are several (usually numbered as seven) “dispensations,” or ages of the world characterized by differing ways or covenants that God has dealt with Man. For example, the “Old Testament” period from the giving of the Torah at Sinai is considered “the Dispensation of Law,” while the New Covenant period that began with Yeshua’s sacrifice, resurrection, and giving of the Spirit is the “Dispensation of Grace.” In this way, a rationale is given for Christians no longer keeping many of the ceremonial and civil ordinances of the Torah: With the coming of Christ, a new, less-burdensome (as it is perceived by most Christians) dispensation characterized by Grace has replaced the necessary stringency of the Age of Law. In this view, all of the promises made to the natural children of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob still stand and will be fulfilled; the Church, it is held, is a “mystery” that was not fully revealed until the New Covenant was given, a new body that is “neither Jew nor Gentile” which is separate both from the nations and from Israel. Many interpret this to mean that God will not really begin to work with Israel again until the Church is taken out of the world in the event popularly known as the Rapture.

Both of these theologies are largely correct in what they assert, but wrong in what they deny. Supersessionism is correct that the Church (which is to say, the Gentile followers of Israel’s Messiah) cannot be simply separated from Israel, that they have become citizens and heirs of Israel’s promises, and even that we may consider the Church a kind of “spiritual Israel.” However, it is wrong in arrogantly asserting the Church to be a replacement Israel or that the Eternal One has rejected “Israel of the flesh” forever. It is especially wrong in blithely assuming that only Israel’s blessing could come to the Church and that its curses for disobedience are only and always poured out upon the Jews.

Dispensationalism in turn is correct in asserting that the Eternal Covenant-Maker has not forever forsaken the Jewish people and that all of Israel’s promises will be kept to her exactly as given. It is correct in seeing the miracle of the resurrection of a nation in the modern state of Israel. It is wrong in assuming that this must mean that the Church is wholly separate from Israel.

Both sides have grievously erred in how they have dealt with believers of Jewish birth.

Rather than explore the weaknesses of both systems (there is no shortage of arguments against both sides for those who wish to look), let us explore a third, overlooked alternative: that the correct way to understand the relationship of the Church to Israel is not as any Christian having replaced any Jew nor as the Church being wholly separated from Israel, but rather as the Gentile Christians having been adopted into Israel as brothers and sisters to the Jewish people.

1Michael Vlach, “Defining Supersessionism,” retrieved from http://theologicalstudies.org/resource-library/supersessionism/324-defining-supersessionism on February 17, 2013

2Michael Vlach, “What Is Dispensationalism?” retrieved from http://www.theologicalstudies.org/resource-library/dispensationalism/421-what-is-dispensationalism on February 17, 2013

OK, this is annoying, all these little posts that mean I have to wait for the next one.

I am Reformed, Covenantal, but just recently got accused of being dispensational because of my views on Israel. Sigh.

I would be interested in your take on my post on Acts 21.

LikeLike

Yeah, well, that seems to be the best way to keep you coming back and make my stats look better. And I think you’ll find that the direction I’m taking this will help resolve the tension you are experiencing between your Covenant Theology and support for Israel.

Can you give me a link for your article? I’d love to see it, especially since I consider Acts 21 to be absolutely crucial in understanding Paul’s letters.

Shalom

LikeLike

Well, sure. especially as that might make my stats look better ;) Didn’t want to post without permission:

http://vonstakes.blogspot.com/2010/08/acts-21-first-post.html

Seriously feel free to comment, I love comments.

LikeLike

I’m at work, so I could only glance very quickly at the first few sentences, but I think I’m going to like your post. :)

Out of curiosity, have you caught the rather blatant mistranslation in verse 20?

LikeLike

Two posts, actually. And for some reason the first one is my far and away most popular post.

Acts 21:20? Thousands?? Should by myriads or ‘tens of thousands’??

Oh, and it would be interesting to get your take on my most recent baptism debate.

http://vonstakes.blogspot.com/2013/03/the-squirrel-vs-penguin-debate-on.html

LikeLike

Controversy always gets attention. And yes, that’s it. I’ll be curious to see what you make of Christian translators routinely botching such a simple word in order to underplay the number of Jewish believers by an order of magnitude.

LikeLike

I had heard of that, but didn’t focus on it in this article. It take aim at the prevailing view that Paul, Luke, James, et. al. were wrong in Acts 21; that the Jewish believers were weak, Judiazers, etc.

LikeLike

Have you written anything on Acts 10-11?

LikeLike

Sorry for the delay. No, not as such. I probably should.

LikeLike